Counterexample to Theorem 5-2

by Hidenori

Proposition

Find a counterexample to Theorem 5-2 if condition (3) is omitted. [Spivak]

Solution

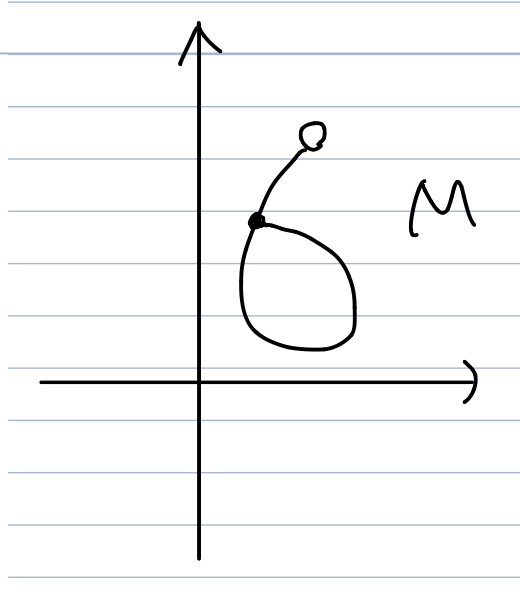

Consider the following manifold which can be obtained from wrapping $(0, 1)$.

For any $x \in M$, let $U = \mathbb{R}^2$ and $W = (0, 1) \subset \mathbb{R}^1$. Then the function $f(t) = (f_1(t), f_2(t))$ which simply maps the interval $(0, 1)$ into the figure 6 is a differentiable.

- Clearly, $f(W) = M \cap U$.

- $f’(t) = (f_1’(t), f_2’(t)) \ne 0$ because at each point at least one of $f_1$ or $f_2$ is strictly increasing or decreasing. This implies that the rank of $f’(t)$ is 1 at any point because it is a nonzero $1 \times 2$ matrix.

Therefore, it suffices conditions (1) and (2) in Theorem 5-2.

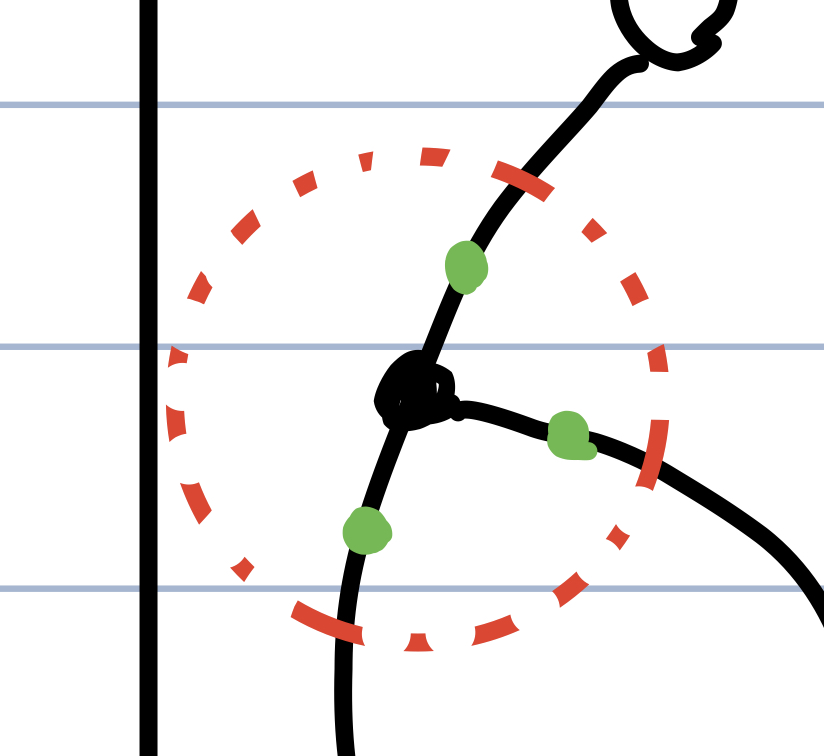

We claim that $M$ does not satisfy the definition of a manifold on P.109[Spivak].

Let $x \in M$ be the point at the intersection. If $M$ is a 1-dimensional manifold, there must exist an open set $U$ and open $V \subset \mathbb{R}$ with a diffeomorphism $f:U \rightarrow V$ such that $h(U \cap M) = V \cap (\mathbb{R}^k \times { 0 })$.

No matter what $U$ is, we are always able to obtain three points in three different “branches” as shown in the figure above. Let $v_1, v_2, v_3$ denote them in no particular order. Without loss of generality, we will assume $f(x) = 0$. Then $0 \notin \{ f(v_1), f(v_2), f(v_3) \}$ because $f$ is bijective. Then $\sgn(f(v_i)) = \sgn(f(v_j))$ for some $i \ne j$ because there are only two signs. Without loss of generality, assume $0 < f(v_1) < f(v_2)$. However, this implies that $f$ is not bijective because $f$ maps $v_1$ and some point in the line between $x$ and $v_2$ to the same value. This is a contradiction, so $M$ is not a $1$-manifold.

Subscribe via RSS