$\mathbb{R}^2$ is not homeomorphic to $\mathbb{R}^n$ for $n \ne 2$

by Hidenori

Proposition

$\mathbb{R}^2$ is not homeomorphic to $\mathbb{R}^n$ for $n \ne 2$.

Solution

Let $f: \mathbb{R}^2 \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^n$ be a homeomorphism.

Then the restriction $f_{\mathbb{R}^2 \setminus 0}$ is a homeomorphism from $\mathbb{R}^2 \setminus \{ 0 \}$ into $\mathbb{R}^n \setminus \{ f(0) \}$. $\mathbb{R}^n \setminus \{ f(0) \}$ is homeomorphic to $\mathbb{R}^n \setminus \{ 0 \}$ because the linear shifting function is a homeomorphism. Thus we have a homeomorphism, say $g$, from $\mathbb{R}^2 \setminus \{ 0 \}$ into $\mathbb{R}^n \setminus \{ 0 \}$.

Suppose $n = 1$.

- $\mathbb{R} \setminus \{ 0 \} = (-\infty, 0) \cup (0, \infty)$. It is disconnected, and thus it is not path-connected.

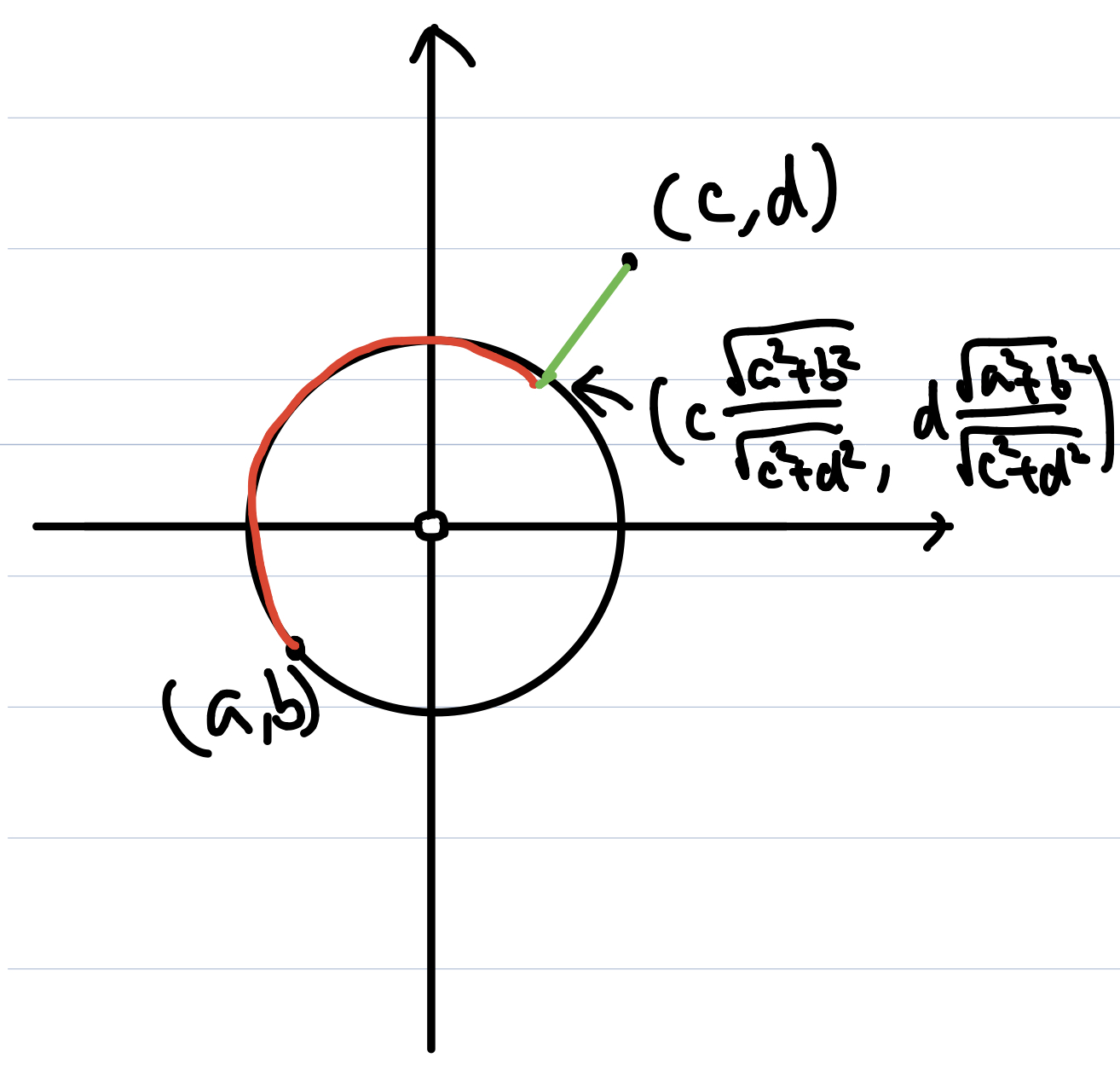

- Let $(a, b), (c, d) \in \mathbb{R}^n \setminus 0$.

Then every point on the circle $x^2 + y^2 = r^2$ can be joined by a path where $r = \sqrt{a^2 + b^2}$.

Then $(a, b)$ and $(c\frac{r}{\sqrt{c^2 + d^2}}, d\frac{r}{\sqrt{c^2 + d^2}})$ can be joined by the circle.

Moreover, $(c\frac{r}{\sqrt{c^2 + d^2}}, d\frac{r}{\sqrt{c^2 + d^2}})$ and $(c, d)$ can be joined by a straight line.

Thus $(a, b)$ and $(c, d)$ are path-connected, so $\mathbb{R}^n \setminus 0$ is path-connected.

This is a contradiction, so such a homeomorphism does not exit.

Suppose $n \geq 2$.

We will first prove that $\mathbb{R}^k \setminus \{ 0 \}$ is homeomorphic to $S^{k - 1} \times \mathbb{R}$ for any $k \geq 2$.

Consider $f(x_1, \cdots, x_k) = ((x_1 / r, \cdots, x_k / r), \log r)$ where $r = \sqrt{x_1^2 + \cdots + x_k^2}$, and $g((y_1, \cdots, y_k), y) = (e^yy_1, \cdots, e^yy_k)$. Then $f$ maps $\mathbb{R}^k \setminus \{ 0 \}$ into $S^{k - 1} \times \mathbb{R}$, and $g$ maps $S^{k - 1} \times \mathbb{R}$ into $\mathbb{R}^k \setminus \{ 0 \}$. $f, g$ are both continuous.

\[\begin{align*} f(g((y_1, \cdots, y_k), y)) &= f(e^yy_1, \cdots, e^yy_k) \\ &= ((e^yy_1 / r, \cdots, e^yy_k / r), \log r) \end{align*}\]where $r = e^y\sqrt{y_1^2 + \cdots + y_k^2} = e^y$. Therefore, $f(g((y_1, \cdots, y_k), y)) = ((y_1, \cdots, y_k), y)$.

\[\begin{align*} g(f(x_1, \cdots, x_k)) &= g((x_1 / r, \cdots, x_k / r), \log r) \\ &= (x_1, \cdots, x_k). \end{align*}\]Since $f \circ g$ and $g \circ f$ are both the identity function, $f$ is both injective and surjective. Therefore, $f$ is a homeomorphism.

Now this result implies that:

- $\pi_1(\mathbb{R}^2 \setminus \{ 0 \}) \approx \pi_1(S^1 \times \mathbb{R})$. By the proposition shown in this post, This is isomorphic to $\pi_1(S^1) \times \pi_1(\mathbb{R})$. Since $\pi_1(\mathbb{R}) = 0$, this is $\pi_1(\mathbb{R}^2 \setminus \{ 0 \}) \approx \pi_1(S^1) \approx \mathbb{Z}$.

- $\pi_1(\mathbb{R}^n \setminus \{ 0 \}) \approx \pi_1(S^{n - 1} \times \mathbb{R})$. Using the same argument as above, we know that $\pi_1(\mathbb{R}^n \setminus \{ 0 \}) \approx \pi_1(S^{n - 1})$. We proved in this post $\pi_1(S^{n - 1}) = 0$ since $n \geq 3$.

Since $\mathbb{Z} \not\approx 0$, this is a contradiction. This implies that such a homeomorphism does not exist.

Subscribe via RSS